Sunshine Week (or Why "State Secrets" Suck)

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) was intended to make the federal government more transparent. Its author would be appalled at how courts have eviscerated it. Congress should fix it.

Whenever the people are well informed, they can be trusted with their own government; that whenever things get so far wrong as to attract their notice, they may be relied on to set them to rights. Thomas Jefferson to Richard Price, January 8, 1789

A little over 175 years after Jefferson's letter to Price, a California Democrat succeeded bringing Jefferson's vision of a more open, transparent government into being.

The man in question was Rep. John Moss (D-CA) and the mechanism to increase citizen access to government records was the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA).

As chronicled in Michael Lemov's 2011 People's Warrior, prior to the FOIA's enactment in 1965 Moss had spent the better part of his first decade in Congress battling multiple federal agencies and departments for information about their operations and actions. Things as mundane at telephone directories or as serious as federal agencies misuse of funds were being withheld not only from public release, but release to Congress as well.

In a series of landmark hearings between 1955 and 1965, Moss steadily built the case for creating a statutory information pry-bar that, in theory, could be used by any citizen to shake loose information about what the federal government was doing with their tax dollars and in their name. President Lyndon Johnson threatened to veto the bill but ultimately relented.

In the nearly six decades since the FOIA's enactment, it's been amended multiple times--in every case to deal with either federal court decisions that have circumscribed its reach, to overcome federal agency or department obstructionism, or both. In 2005, a national "Sunshine Week" was established to both celebrate the FOIAs achievements and call for improvements to the law and for federal components to stop stiff-arming requesters.

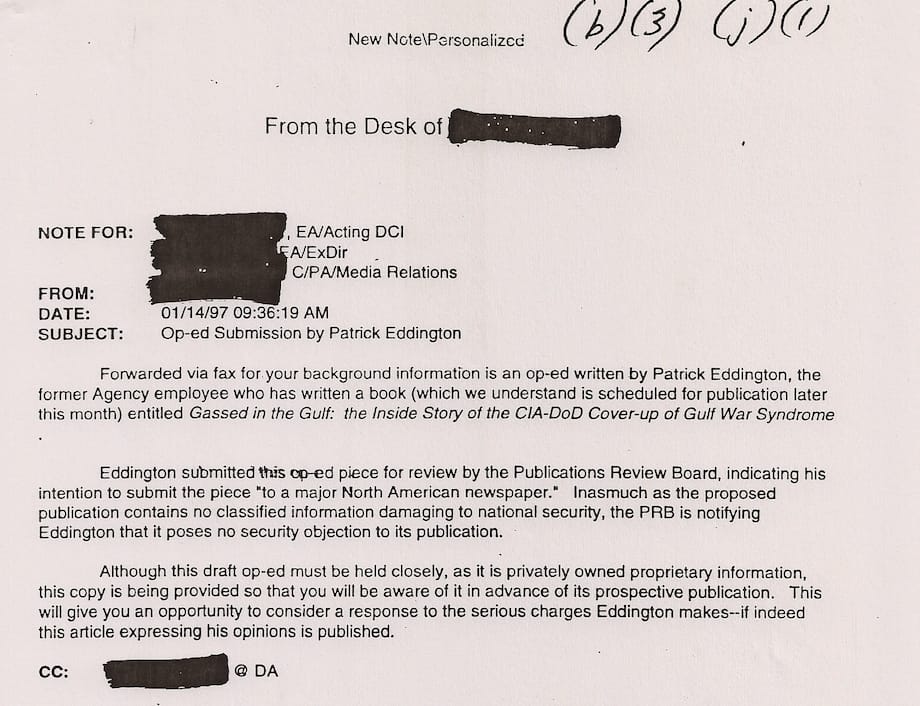

As the lead image for this piece makes clear, I've had my own experiences dealing with federal agency/department responses to FOIA requests I've submitted over the last 30+ years. Indeed, I was investigated by CIA's Office of Security (OS) for alleged media contacts (I'd had none at that point) in connection with CIA and DoD attempts to downplay or even dismiss potential or actual chemical agent exposures among Operation DESERT STORM veterans.

I knew at the time that OS was investigating me because colleagues who were queried about my "loyalty to the Agency" let me know about their interviews. Via subsequent FOIA litigation, I obtained the documents cited earlier and a whole lot more, a portion of which I worked into my 2011 book, Long Strange Journey: An Intelligence Memoir.

But a lot has changed with FOIA and its utility in the nearly 30 years since I left the CIA, and most of it not for the better.

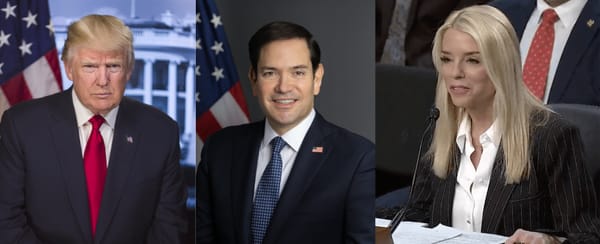

As I noted in my testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee last year:

During the Clinton administration, the FBI would again open, in secret, a nationwide investigation without a valid criminal predicate, this one targeting Arab and Muslim Americans in the Chicago area under the code name VULGAR BETRAYAL. One of the reasons the full details on this FBI surveillance scandal remain unclear is because the Bureau has only provided Cato roughly 35,000 of the nearly 1.3 million pages of material it has on the episode.18

Unfortunately, Cato had to abandon that FOIA request. The reason is that since the Bureau will never release more than 500 pages per month to a FOIA requester in the D.C. Circuit (absent the very rare order from a federal judge to produce more per month), it would take 215 years for Cato to receive all the records. This is a de facto form of constructive denial of Cato’s request. It also allows the Bureau to continue to hide the magnitude of its misconduct and failures in the VULGAR BETRAYAL episode.

The situation is as bad or worse with the federal government's other records declassification program, known as the Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) process, which is overseen by the federal Information Security Oversight Office (ISOO). Again, from my HSGAC testimony, quoting from a report from then-ISOO Director Mark Bradley:

In ISOO’s 2021 annual report to President Biden, Bradley noted the need to overhaul, if not eliminate, the automatic declassification system currently in use because it “is unable to meet the requirements for existing paper records and will never keep up with the tsunami of digital CNSI [classified national security information] being created daily, making it likely that most of it will never be reviewed for declassification.

What Bradley is predicting is that without fundamental, enforced changes in record keeping and classification practices at the federal level, America will have a permanent secret history, one that will be completely impenetrable by the citizens of this country.

Federal courts have also compounded this problem through judicial activism that has created Executive branch secret-friendly doctrines like the “state secrets privilege,” which allows the government to withhold information from public release in the name of “national security.” There is no textual basis for this court-created doctrine in the Constitution, and it remains a government transparency bane to this day. While some House members have offered bills to effectively nullify the doctrine, none have ever passed out of a committee, much less made it to a vote on the floor of the House or Senate.

In my 2023 testimony before HSGAC, I outlined a detailed, perfectly workable reform proposal that, if implemented, would eradicate most of the problems I’ve just described. If you’re in a “TL;DR” mood & don’t want to read my whole testimony but just the legislative fix, just pull up the testimony and “Search in page” for “A Classification and Records Management Reform Proposal.”

However, I don’t think it’s enough to simply change laws and hope for the best. We don’t just need different and better government transparency and accountability statutes—we need better people in government, especially the courts, to ensure their enforcement.

Based on more than two centuries of experience in our national republican experiment, I think Thomas Jefferson's observation to Richard Price needs significant revision. I'd suggest something along these lines:

"Whenever those in government hide its actions from the people it was created to serve, either through deliberate practice or dereliction and neglect, and in so doing places the rights of the people at risk, such government officials are unworthy of the people's trust and loyalty, and thus should be expelled from office."

Thanks for reading. If you find the Sentinel informative, please share it with your colleagues, friends, and family.