Nothing "Great" About It: World War I, the Rise of the American National Security State, and the Espionage Act

The "Great War" ushered in the modern national security apparatus, and with it, a secrecy law as draconian as it is ineffective at protecting real secrets

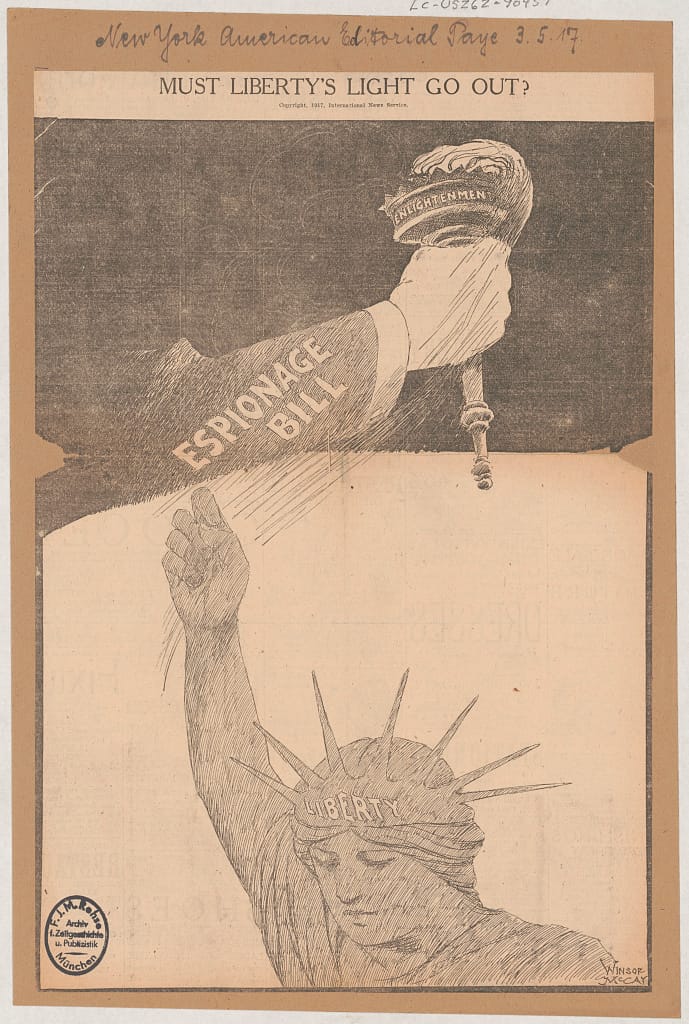

This coming Saturday, April 6, will mark the 107th anniversary of America's entry into what at the time was known as "The Great War"--what we know today as World War I. Many inventions of war we take for granted today--the machine gun, the airplane, the submarine, chemical weapons--got their first real-world tests at scale in a conflict that would ultimately claim lives of more than 30 million combatants alone. Something else emerged from the conflict that also got its first tests during the war and many times since--the Espionage Act.

Last year, Basic Books published the first major account on the history of the now-infamous law by George Mason history professor Sam Lebovic. In State of Silence: The Espionage Act and the Rise of America's Secrecy Regime, Lebovic notes (p. 6) that the key sections of the Espionage Act were "largely copied from an earlier Defense Secrets Act, itself rushed through Congress six years before." The most dubious part of the Espionage Act (codified at 18 U.S.C. § 793) is the one that's actually been used to go after newspaper publishers (Victor Berger of the Milwaukee Leader in World War I, also the first socialist elected to Congress) and government officials who leak classified information to newspapers (the late Daniel Ellsberg being the most famous).

The government ultimately lost both of those cases, but it's been successful in others. Most Espionage Act cases have been brought against individuals even when no actual espionage against the U.S. was involved. That was the case with Berger and Ellsberg and it has also been true in more recent cases involving Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, former FBI Agent Terry Albury, and former NSA contractor Edward Snowden. Instead, the charging of the individuals in question appears linked to their exposure of U.S. government misconduct or outright criminality.

In Albury's case, it was for exposing the FBI's dirty laundry with respect to its pattern and practice of engaging in racial or religious targeting of Arab or Muslim Americans in bogus terrorism-related investigations. The 11 stories The Intercept published that relied on Albury's disclosures revealed an FBI every bit as out of control as it was during J. Edgar Hoover's tenure. But instead of FBI officials being impeached, fired, or prosecuted for their misconduct, it was Albury who was prosecuted under the Espionage Act. He took a plea deal in 2018 and served about two years of a four-year sentence.

Edward Snowden of course has also been charged under the Espionage Act. His "crime" was exposing, among other things, the massive telephone metadata dragnet run by the NSA with the help of telecommunications companies like Verizon that encompassed the phone traffic of millions of Americans. Snowden's actions would also lead Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) officials to kill a similar program they'd been running since at least 1992, one even some DEA lawyers and FBI agents thought was likely unconstitutional--though the public would not learn about that until years after Snowden's initial revelations. Snowden remains in exile in Russia to this day.

But before Albury or Snowden, there was Chelsea Manning and Julian Assange.

While an Army Intelligence enlisted member, Manning provided Wikileaks and Assange with, among other things, clear video and related evidence of U.S. military war crimes in Iraq during the Bush 43 administration, specifically the murder of civilians and journalists working for Reuters by U.S. Army AH-64 Apache attack helicopters. The incident, captured on the video Manning gave to Wikileaks, became known as the "Collateral Murder" video.

Manning also released to Wikileaks over 90,000 pages of Army Afghan war logs, 400,000 American military reports from the Iraq war, and a quarter of a million State Department cables. The U.S. national security bureaucracy all but lost its mind over those leaks, but as Lebovic notes (pp. 336-337), "a 2011 Pentagon task force on Wikileaks concluded that no one had suffered physical harm as a result of the leak, and no such instance has come to light in the decade since." Then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates also conceded that the document dumps were "embarrassing" and "awkward" but could point to no lasting damage to U.S. credibility or influence with its allies.

It was a back-handed admission that more often than not, the U.S. document classification system is used to hide government ineptitude, bungling, or criminal conduct.

Manning was betrayed by a fellow hacker, Adrian Lamo, and charged under the Espionage Act. Starting in 2013, she began serving what was originally a 35-year sentence for being found guilty of multiple Espionage Act violations. A small but vocal advocacy campaign on her behalf, and perhaps also the revelations about her two suicide attempts in 2016, may have had some role in President Obama's decision to commute her sentence in 2017.

Assange was also charged by the U.S. government under the Espionage Act, and as I write these lines is making what could be his last legal stand in England, trying to avoid extradition to the United States to face trial. I've never considered Assange to be a particularly sympathetic figure, but the reality is that his case and the others I've discussed represent what can only be considered a pattern and practice by the U.S. government of waging "lawfare" against those intent on exposing the government's own crimes.

No U.S. government employee--civilian or military--has ever been charged in connection with the "Collateral Murder" incident. No FBI employee has, to the author's knowledge, ever been fired for engaging in the kind of surveillance or related activity exposed by Albury. And instead of ending the warrantless electronic dragnet surveillance exposed by Snowden, federal officials have succeeded in making the practice all but permanent.

Indeed, even though a long-standing executive order prohibits misusing the classification system to hide waste, fraud, abuse, mismanagement, or even criminal conduct, there is no statute that actually bans the practice. Until that changes, and until we have real and effective whistleblower protection law in place (like this proposal), federal officials will continue to misuse the classification system to hide their misconduct...and the Espionage Act will remain their shield and sword against those who try to expose the government's crimes.

Thanks for reading the Sentinel. If you're not currently a subscriber, please consider becoming one. Also, if there's a particular topic or issue you'd like to see me cover, just let me know via the comment section.