Compromised Overseers: A Department of Justice Story

When the Inspector General Act was passed in 1978, its backers hoped it would usher in a new age of government oversight. A case involving the Justice Department demonstrates that was magical thinking

When I began this publication in January, I noted that the focus would be on two types of threats to constitutional rights: political and institutional. This week and as part of an occasional series I'm calling "Compromised Overseers," I'm presenting a case study on one of those institutional threats: the fundamental weakness of the federal inspector general system. First, a little historical background.

Internal Oversight Reform: Hope v Reality

In the wake of the Church Committee's investigation of domestic surveillance and political repression activities carried out by multiple federal agencies and departments during the Cold War, four legislative proposals were enacted in the hopes of forestalling future constitutional rights violations. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) and the related Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), as well as the creation of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence (HPSCI) and Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI), were three of those legislative enactments. FISA and the FISC were supposed to prevent unconstitutional government surveillance from being approved in the first place. HPSCI and SSCI were supposed to prevent potential unconstitutional programs from even getting started and act as the Article I constitutional overseers of the Executive branch that the Founders intended.

The Inspector General Act of 1978 was the fourth and most novel reform proposal, creating supposedly independent inspector general offices in every major agency and department of government. The theory behind the IG Act was that by creating dedicated audit and investigation arms within the Executive branch components, it would make it less likely that waste, fraud, abuse, mismanagement, or overtly illegal activity would take place--and if it did, it would be caught and stopped.

A case can be made that when it comes to investigating white collar crime inside Executive branch agencies and departments, the IG Act has probably had at least some positive impact, though the effects are often couched as "potential savings." But when we look at episodes in which Executive branch components have engaged in activities that violate constitutional rights--either at the behest of their leadership or on orders from the White House--we often find that IG's were either kept out of the loop or discovered unconstitutional activity long after the fact.

To that point, a relatively recent scandal involving the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) and the Department of Justice Inspector General (DoJ IG) is highly illustrative.

"War on Drugs" Surveillance Programs Run Amok

On April 7, 2015, USA Today ran a story with the headline, "U.S. secretly tracked billions of calls for decades." As reporter Brad Heath noted at the time

The now-discontinued operation, carried out by the DEA's intelligence arm, was the government's first known effort to gather data on Americans in bulk, sweeping up records of telephone calls made by millions of U.S. citizens regardless of whether they were suspected of a crime. It was a model for the massive phone surveillance system the NSA launched to identify terrorists after the Sept. 11 attacks. That dragnet drew sharp criticism that the government had intruded too deeply into Americans' privacy after former NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked it to the news media two years ago.

Nine days after that story ran, I filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the Justice Department seeking records on the "USTO" program Heath identified in his piece. Nearly two years passed while DoJ and the DEA slow-rolled my FOIA request. Then in March 2019, the DoJ IG issued a "Redacted for Public Release" version of an investigative report titled, A Review of the Drug Enforcement Administration's Use of Administrative Subpoenas to Collect or Exploit Bulk Data.

The main program--dubbed USTO--was authorized in January 1992 by then-Attorney General William Barr. It was terminated in 2013 after Edward Snowden's revelation of a nearly identical National Security Agency (NSA) program. There is no public evidence I am aware of indicating that Barr or any of his successors ever informed the DoJ IG about the existence of these programs prior to 2013.

The report was relatively critical of DEA for running the three programs under "administrative subpoena" authority vice seeking court authorization for the activity, and for the sheer volume of data it collected and shared, often without any clear nexus to violations of federal laws. The report revealed that DEA tried to get Justice Department officials to let them resume the USTO program in its original form, but Justice leadership refused.

When I read the IG report, I was extremely concerned about the level of redactions in a document that described programs that were not classified at any point. I decided to put in FOIAs for the non-public version of the IG report and the 175,000 documents investigators said they examined.

Almost three more years passed before I got that non-public version of the March 2019 report, which had been administratively labeled "Law Enforcement Sensitive" (LES)--a term not recognized in the FOIA statute but frequently employed by federal law enforcement organizations to keep otherwise unclassified information about police activities from public release.

But the LES version of the DoJ IG report didn't come from the DoJ IG itself, but instead from the agency it investigated--DEA. That was an immediate red flag for me.

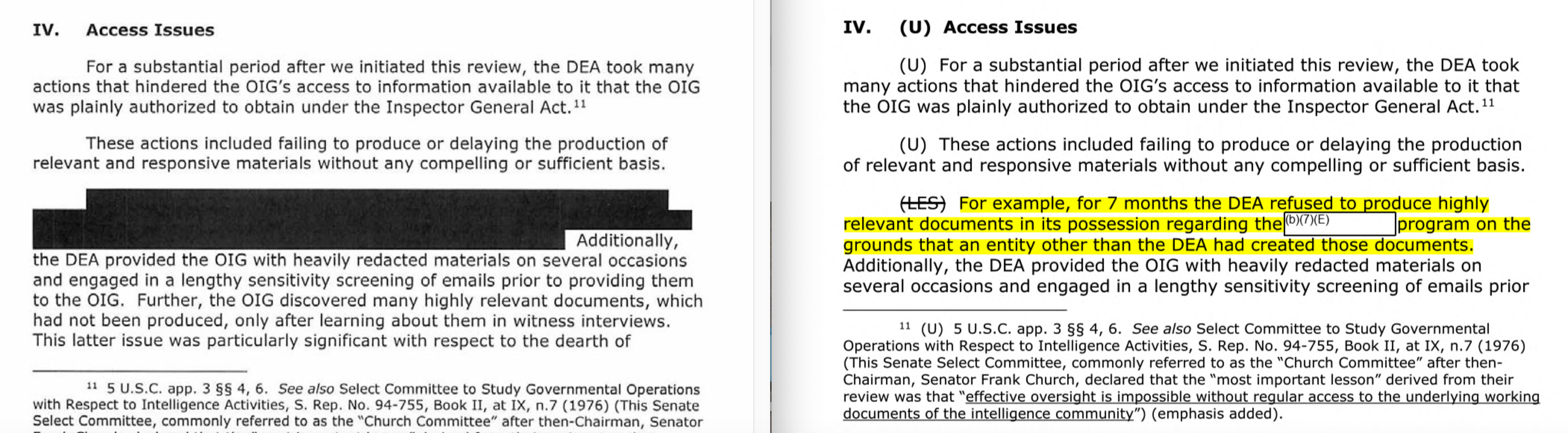

As I did a side-by-side comparison of the two versions, it became clear that both the IG and DEA had concealed critical information from the public about DEA's misconduct--not just during the 20+ year lifespan of the USTO program, but after the IG began its investigation of DEA itself.

One of the most remarkable things kept from the public in the March 2019 DoJ IG report was the fact that DEA refused to cooperate with the IG for 7 months in direct defiance of Justice Department policy. There was no mention of administrative action or criminal charges filed against DEA personnel for defying the IG (p.5).

The IG and/or DEA also withheld from public release in 2019 specific provisions of the DEA Agents Manual that shed critical light on the sweeping power granted line DEA agents to employ administrative subpoenas--a recipe for the abuse at scale that subsequently took place for over 20 years. (pp. 12-14)

The word "purchase" or its derivatives appears only 37 times in the publicly released version of the IG report, but 55 times in the LES version released to me. When linked to references to "devices" or "device purchases," it's clear that this is about bulk data on "burner" phone purchases.

Even FBI agents offered access to this kind of data were concerned that it might be deemed illegally obtained by a federal court should the program come to light. One of the FBI agents interviewed by the IG was quoted on p. 69 of the report as follows:

[But] you can't just take any [kind of] innocent activity that Americans engage in and go grab all their records knowing that a small percentage of it is potentially connected to illegal activity. And that sounded exactly like what DEA was looking to do.

In theory, DEA was supposed to only collect this kind of data pursuant to an actual, legitimately predicated investigation under a legal standard known as reasonable articulable suspicion (RAS). The DoJ IG did raise this issue in its publicly released report in March 2019, but not everything it knew about DEA's failed RAS compliance record was included in that version. Additional details about DEA's internal RAS audit trail insufficiency kept from the public in March 2019 were revealed in the LES version released to me. (pp. 29-30)

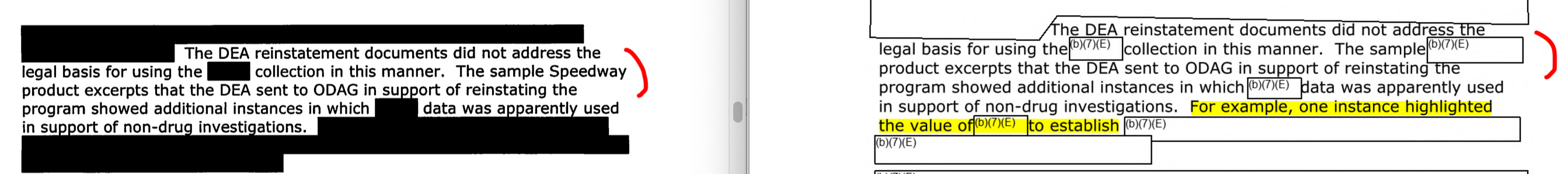

One of the names of an intelligence product line created based on data from the three DEA progams, Speedway, was revealed in the publicly released report in March 2019. However, DEA REDACTED in the LES version released to me the reference to the Speedway intelligence product--a practice not allowed under the FOIA statute. (p. 23)

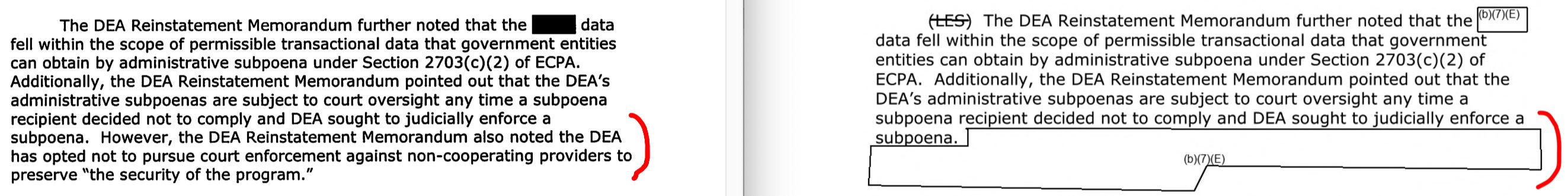

DEA also redacted in the LES version released to me an entire sentence made public in the March 2019 version of the report: "However, the DEA Reinstatement Memorandum also noted the DEA has opted not to pursue court enforcement against non-cooperating providers to preserve "the security of the program." (p. 37) None of the DEA programs were classified under Executive Order 13526. What DEA was trying to protect was the fact that its surveillance programs were illegal.

Also of note was the likely use of USTO bulk data in investigations having nothing to do with narcotics, with the IG noting the data "was sometimes queried with target phone number relevant to non-drug investigations, including terrorism cases and the Hassanshahi trade embargo case..." (p. 42) Unanswered was whether those non-drug related investigations were lawfully predicated. How many times did the DEA going on electronic fishing expeditions in non-drug cases the absence of valid criminal predicate? The report does not say.

Compromised Oversight

The fact that the DoJ IG let the DEA redact and release the IG's own investigative report on the agency isn't simply shocking--it calls into question the entire premise that the DoJ IG is, in fact, capable of carrying out its core mission of independent oversight of DoJ components.

How many other times has the DoJ IG allowed a DoJ component it investigated to redact information showing incompetence, negligence, deliberate stonewalling, or even constitutionally questionable or demonstrably illegal activity?

We don't know, because no other governmental entity--including the Congress--is engaged in a systematic program over "overseeing the overseers." And while civil society organizations and the press employ FOIA to try to answer some of those questions, using FOIA is time consuming and more often than not requires litigation in order to force agencies or departments to produce requested documents. Changing that paradigm means changing federal law.

A place to start would be to mandate that when an agency or department being investigated by an IG puts up investigative roadblocks or outright subverts an investigation, the IG must make a criminal referral to the U.S. Attorneys Office. Fear of prosecution can be a powerful incentive for people to cooperate with a legitimately predicated investigation.

Thanks for reading the Sentinel. If you're not a subscriber, please consider becoming one today. I’ll be back next week with my review of Michael Glennon’s new book, Free Speech and Turbulent Freedom: The Dangerous Allure of Censorship in the Digital Era.