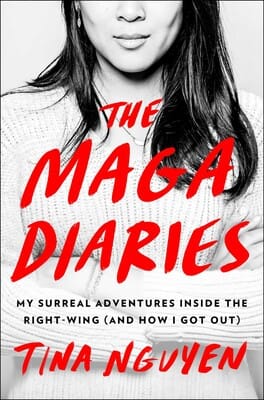

Book Reivew: "The MAGA Diaries" by Tina Nguyen

A misleadingly titled book saves the best political and historical insights for the footnotes

Well told, personal odyssey stories of discovery--self-discovery and discovering the larger world--can be entertaining, occasionally even enlightening. Tina Nguyen's The MAGA Diaries does not quite fall into that category. For one thing, she never worked for Donald Trump. Hence, the misleading title.

To be sure, there's lots of recollections of youthful angst: about whether she would get that plum journalism internship that would jump start her career; being raised in a single parent household by her taciturn Vietnamese immigrant mother; regrets about an epically bad choice in romantic partners. And the name-dropping is continuous: from Alan Dershowitz to Tucker Carlson and lots of other in between.

The book is also riddled with banal, useless details in a forced attempt to give the narrative a "you are there" vibe:

I'd chugged my Starbucks, left my room at the Embassy Suites, taken the disconcertingly open-glass elevator down a vertigo-inducing eighteen stories to the lobby, and darted across the street with my phone out. (p. 2)

I'd taken the Amtrak from DC to Philadelphia, the SEPTA train to the suburbs, and arrived at the secluded, misty Bryn Mawr campus aglow. (p. 47)

I put on my nicest outfit, dressed to impress, and teetered on high heels off the DC Metro escalator, up two blocks to the entrance of the Capitol Hill Club, where a woman asked for my name and who I was visiting. (p. 62)

There's lots of this kind of stuff, but I'll spare you the other examples.

But the most bizarre thing about this book--which is supposed to be about her entry into and journey through the conservative movement of the late Bush 43 administration onward--is how some of the most important and key details about that movement and its underpinnings are stashed away in the endnotes.

She actually has pretty good summaries of the overall philosophies of people like Edmund Burke, Adam Smith, and several others in those endnotes. Maybe she wanted to include that material in the chapters themselves and she got overruled by the folks at One Signal Publishers (a Simon & Schuster imprint). Or maybe she thought incorporating that kind of intellectual context would turn off some readers looking for a breezy if lightweight read. Whatever the reason, the choice was a bad one, as it made me wonder exactly what she really thought of the ideas of those thinkers as she was confronting them in real time as a young person, trying to figure out who she was and what she really believed.

What also struck me about this book was how casually she approached the question of how she actually identified politically. For a job interview with the now-infamous Daily Caller, when asked how she'd characterize herself politically, we read this (pp. 67-68):

"I'd say libertarian," I said brightly, sitting up primly in a green seersucker J. Crew jacket with my ankles politely crossed. Years of Koch-funded intellectual and professional training had given me quick facility in all things involving libertarian ideology, as well as the ability to present professionally and navigate an interview. At least I hoped it did: this was the first real-world test. "Free market. Freedom of speech. Inalienable rights. All that jazz. I love what you're doing here, by the way."

Scour the index and you'd look in vain for the names of Ayn Rand, Murray Rothbard, or Robert Nozick--all paragons of the libertarian intellectual movement which, to be charitable, has a checkered history.

Rand, the great advocate of pursuing individual self-interest, was an active, enthusiastic collaborator with the odious House Un-American Activities Committee and a genuine fan of J. Edgar Hoover. Rothbard's descent into a racist mentality culminated in his embrace of David Duke. Nozick, whatever one might think of his ideas, was at least an interesting intellectual.

But to claim as Nguyen does a "quick facility in all things involving libertarian ideology" without once citing its key thinkers--the Koch's embraced the ideology but were not original thinkers themselves--leaves one with the impression that her familiarity with the movement she claimed to be a part of was only interview level-deep.

Her account of her job travails and coming-of-age in and ultimately escaping what her former Daily Caller colleague Matt Lewis called "the conservative media ghetto" is insightful in the historical and personal sense. This one (p. 100) is a gem:

I hadn't fathomed that I could get any lower than laundering right-wing talking points through a fake newspaper in Wisconsin.

It would get worse, for a brief time, but Nguyen eventually landed on her feet, covering the very movement she ultimately left behind...a movement I don't think she was ever really a part of or embraced in a meaningful, substantive way. For me, that's the best part of her story: she awoke from her madness and fled, despite the short-term professional and financial cost.