America's Citizen Government Oversight Tool: The Freedom of Information Act Nears Sixty

Enacted on Independence Day 1966, the venerable open government law is hated by federal bureaucrats who waste no opportunity trying to find new ways to thwart its use. While still a valuable government oversight tool, FOIA needs rejuvenation if it is to remain viable.

Enacted on Independence Day 1966, the venerable open government law is hated by federal bureaucrats who waste no opportunity trying to find new ways to thwart its use. While still a valuable government oversight tool, FOIA needs rejuvenation if it is to remain viable.

California Democrat John Moss was one of those people with a knack for beating the odds. In the 1952 national elections in which Republicans gained control of the White House, Senate, and House, Moss managed to win a nail-biter of a contest to reach the House of Representatives. From his new position on the House Committee on the Post Office and Civil Service, Moss would attempt but fail to get the Civil Service Commission (CSC) to release the reasons for the release of nearly 3000 federal employees on "security" grounds under the so-called federal "Loyalty Program"--an action that appalled Moss.

In recounting the Moss-CSC confrontation over the records, author Michael Lemov noted in People's Warrior: John Moss and the Fight for Freedom of Information and Consumer Rights,

Moss was not a person who liked to be stymied, particularly in an area where he believed he was acting within his rights. He did not forget the issue or the afront. (p. 48)

Within two years, House Speaker Sam Rayburn (D-TX) would give Moss the chairmanship of the newly created Special Subcommittee on Government Information on the Government Operations Committee. For the next decade, Moss would use this legislative platform to systematically attack government secrecy and intransigence over records about Executive branch agency and department operations.

His experience led him to understand that those agencies and departments needed to be forced to turn over non-classified information to the public so voters could get at least some understanding of what their tax dollars were being used for, why, and whether or not a given program or activity should be allowed to continue or be ended. His solution was a bill known as the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), and it was, at the time, revolutionary.

The bill required federal agencies and departments to turn over records to the public upon demand unless the agency or department elected to invoke one or more of nine specific exemptions to keep the records out of the public domain. If they did withhold records in part or in whole, the agency or department had to explain to the requester why they had done so and specify how a requester could appeal the initial denial decision. If the denial was upheld by agency/department higher ups, the requester had two choices: accept the outcome or find a lawyer willing to sue in federal court challenging the final denial.

A very reluctant President Johnson signed the FOIA into law on July 4, 1966, but the passage of the statute did little to help Moss himself when confronted with a recalcitrant Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, who six months after FOIA's enactment seemed to take some delight in calling President Johnson to tell him he was stiff-arming a Moss request for aerial photos of alleged civilian casualties in Vietnam.

The statute has been amended no less than eight times, in nearly every case to address new, creative, and outrageous ways that federal agencies and departments developed to try to evade compliance with the statute.

The last such update was in 2016, the key reform being the imposition of the "foreseeable harm" test on government components seeking to withhold data. While well intentioned, the relatively broad and vague language of the change--"the agency reasonably foresees that disclosure would harm an interest protected by an exemption"--still gives agencies and departments too much room to deny release of information to the public.

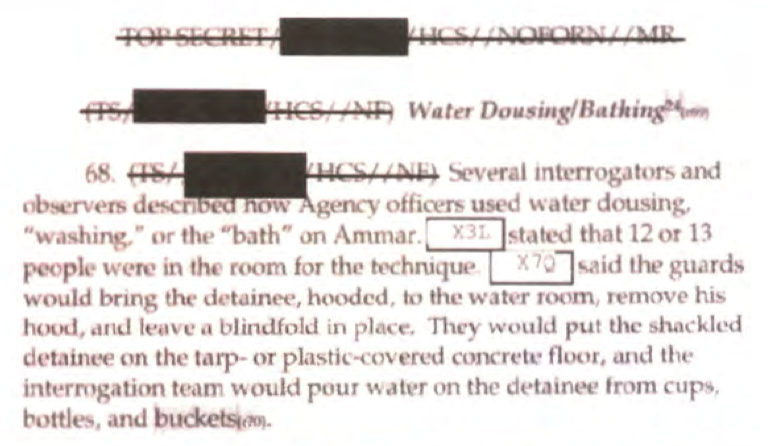

Earlier this year, I wrote about how the "Keep it secret" default mindset of the FBI represents a direct threat to the ability of privacy and civil liberties advocates to get a sense of how sweeping and radical FBI constitutional rights violations are:

Indeed, over the last five years, I’ve documented multiple instances of such FBI rights violations, and in the DSA case noted above and the other ones I’ve written about, the FBI often heavily redacts what it releases under the claim that doing so “would disclose techniques and procedures for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions, or would disclose guidelines for law enforcement investigations or prosecutions if such disclosure could reasonably be expected to risk circumvention of the law.

More often than not, what they’re really trying to hide is the extent, duration, and real reasons for having targeted a particular group in the first place. That practice should be expressly prohibited under a revised FOIA statute. All we need are some House and Senate members willing to take a break from the culture wars or naming post offices and devote some legislative time and energy to revitalizing FOIA so increased government transparency becomes a reality.

And if we do manage to finally get some people in Congress to take a renewed interest in giving FOIA real teeth again, we should also make sure that they also stop wasteful, archaic FOIA processing practices--like sending CDs with only 7 MBs of data on them....or sending CDs at all in the age of the digital download.

Thanks for reading the Sentinel. If you're not currently a subscriber, please consider becoming one as doing so is free through 2024 and it's an easy way to show your support for my work. Also, please share this piece with family, friends, and anyone else you believe would benefit from reading it.